Overview of “Art as Therapy” by Alain de Botton

Art as Therapy, by Alain de Botton and John Armstrong, invites readers to look at masterpieces of art in a new way. Rather than seeing them as simply objects of beauty to be admired, they can also be seen as having therapeutic potential. The book contains chapters on topics such as nature, politics, love and money and explains how appreciating great works of art can have a healing impact on such areas of human life.

Audiocast with Alain de Botton

Both de Botton and Armstrong have written on topics related to philosophy and aesthetics and in Art as Therapy, they present an interesting argument. The book is bolstered by many beautiful illustrations of classic works of art. Even if the authors’ central thesis is debatable and ultimately unprovable one way or the other, it makes for fascinating reading. Those who are well versed in the masterpieces of Western civilization will surely appreciate the possibility that these paintings can have a healing effect on viewers.Readers who are less well informed about art may very well be motivated to make art a greater part of their lives in the future.

Readers on the whole have embraced Art as Therapy as a groundbreaking book that offers people a way to improve their lives. Some reviewers of the book, however, have criticized it as being overly simplistic. One Amazon reviewer, for example, takes issue with the authors’ tendency to interpret paintings outside of their cultural and historic contexts. Many paintings from centuries ago have a religious theme, which de Botton and Armstrong downplay when describing these works. The reviewer questions whether we can take the authors’ interpretations of such paintings at face value without understanding their original meanings.

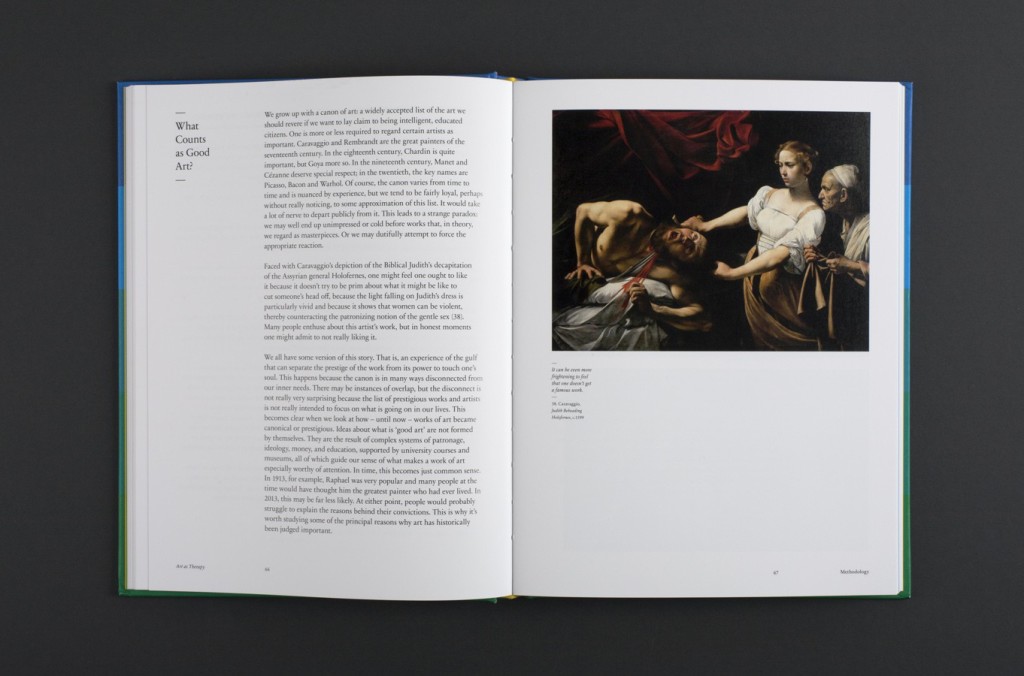

“What counts as good art?” – Sample from Art as Thearpy by Alain de Botton

“What counts as good art?” – Sample from Art as Thearpy by Alain de Botton

Despite some legitimate criticisms, Art as Therapy is a book that can be enjoyed on several levels. It’s a type of self help book, as it offers a way that people can improve their lives. People who are interested in topics such as art history, philosophy and aesthetics will also find much to appreciate in the book, whether they agree with it or not.

The idea that art can be therapeutic is not new. Many colleges even offer degrees in art therapy. This, however, usually involves patients creating art themselves. de Botton and Armstrong are arguing that merely being in the presence of great works of art can have a healing effect. Whether this truly counts as a legitimate form of therapy can be debated. Either way, Art as Therapy is a thought provoking book that can give readers a greater appreciation of art and life in general.

Buy the book:

Art as Therapy Photo Gallery

Art as Therapy Audio Transcript

Speaker 1: A lot of people are familiar with art therapy, the concept of making art as a way of dealing with depression or grief or some other pain. You’ve got a different idea with this book, the idea that there can be a therapeutic value just in looking at art?

Speaker 2: That’s right. This is specifically about the spectator of art, and what they can get out of it. Really that the starting point is so simple, and that is what is the point of looking at art? It’s such kind of naïve question question that sophisticated people like to think well, “Obviously, we always knew that a long time ago.” I just go back to the beginning because I’ve often felt a bit puzzled in museums and in front of works of art.

I just thought how does this fit into my life? What am I allowed to do with this? Is there any sort of good or bad way of behaving in front of this work of art? It’s kind of my belief that, at the end of the day arts, got to in some ways do something for us. It’s a tool, and the book is an attempt to say, okay what sort of tool is it and what it can do for us?

Speaker 1: For example, let’s take a painting everyone knows, the Mona Lisa. What kinds of therapeutic insights might the Mona Lisa inspire?

Speaker 2: First of all, the Mona Lisa is such a difficult painting to have any kind of personal relationship with for the simple reason that it’s so famous.

Speaker 1: It’s also behind about three sheets of glass.

Speaker 2: Right. In other words you’re going to have a very unnatural relationship with it. You have to quieten the noise that surrounds your interactions with the picture. Just ask yourself a very simple question, what do I like about this painting? Let’s imagine, one of the things that’s quite nice about this painting is that the Mona Lisa looks quite nice. Now, that seems really odd and a really sort of stupid thing to say. If you wanted a friend, and you’re looking around, you might think actually this woman, this woman is quite friendly. Why do you think she looks friendly?

Well, there’s something about her eyes and her mouth which seems tender, complicated, slightly humorous but indulgent. She’s sort of a person that you feel like you could tell something, a little bit embarrassing, too. Rather than her judging you or coming in with stinging criticism, she would say, “Okay. I understand. Maybe it wasn’t a great thing to do, but you’re like is complicated.” She seems to be somebody who you can tell a complicated thing to. She’s understood the wisdom of the years and follies of mankind.

Speaker 1: But that’s lovely. Instead of looking at the Mona Lisa as a famous painting, you’re just looking at her as a friend, an interesting person. Then, she’s perhaps helping you access emotions you might then examine in yourself.

Speaker 2: That’s right. This is very much the approach of the book. At one point, we look at a Mother and Child, a beautiful, classical Bellini Mother and Child, you know, there are thousands of them in museums around the world. When you just step back and think, “Okay, what is going on here? Why is it nice to look at this?” This is basically a work of art that is making the idea of hanging out with your mother when you’re about 8 months, and sitting of her lap. It’s reminding you of a deep, primordial joy and sense of security which of course, as we grow up we’re not supposed to be mommy’s boys and girls. We’re supposed to be tough, grown up creatures. But all of us long, particularly at moments of difficulty, when things were not going right, et cetera; we long to go back to that primitive primal cuddle. That’s what one of these great icons of one of the world’s great religions is all about. It’s about the security of childhood.

Speaker 1: It’s almost like getting a little hit of tenderness.

Speaker 2: That’s right, and since that you mentioned the word tenderness because tenderness has got a really low esteem. If you say, “I’m interested in guns, money, fame, power and people think, okay, greatness, you know, great guy.” If you say, “Look, I’m really interested in tenderness,” that sounds so weird. That sounds so odd. But I’m really interested in tenderness. I think there isn’t enough tenderness in the world, and which is separate from mawkishness or sentimentality, or sappiness, or any of these derogatory terms. Tenderness is a due recognition of the vulnerability that is in each of us, of the childlike part that is in each of us. The reason why the Mother and Child was such a popular kind of icon of Western art is that it taps into something psychological that came along way before religion did.

Speaker 1: I’m curious. What would you change about the experience of going to a museum? Right now, let’s say, we go to a famous museum, we walk through the galleries, we stop in front of painting, we read the little tag next to the painting that tells us the artist, the title, maybe when it was painted; is there anything in that you would change?

Speaker 2: Totally. Look, I think the museums have unbelievable prestige in our societies in every big city. In the United States when there’s some surplus wealth, what do people use that surplus wealth for? They give it to the museum. In the same way that in the Middle Ages in Europe, people used to give money to the cathedral. It’s like it’s the place of the highest repository of values. But, when you go into these places, they promise I think to do more than they actually do, and part of the reason is that they’ve been hijacked by an unfair academic agenda. Just think of the way that the rooms are laid out. They’re laid out by things like the Renaissance, the 19th century, Impressionism, of Cubism, et cetera. These are the names of the rooms.

Now, that’s fine if you’re an academic historian. That’s the way that these guys operate, but as an ordinary member of the public, I’m not interested in a room in Cubism just like this. I carry the sort of things that we all care about; interest in work, mortality, friends, family, the country I live in and in the challenges its facing, et cetera. These things come before any interest in the 19th century. If I was in charge of organizing museums which I can tell you a little bit about you because I have been put in charge of a few museums. But, if I was really in charge of museums, what I would do is I would give over sections and rooms to particular themes in our lives.

For example, there would be a room on love. The room on love would put before your eyes a number of works of art that aim to stimulate, provoke, re-enchant, and nourish you in the areas of relationships. One of the works that I’m very keen on is there’s a wonderful, in the National Gallery in London, there’s a picture by Pisano called Daphnis and Chloe which shows a loving couple on the very first night that they’ve been together. It’s incredibly tender and incredibly full of appreciation. I would show any married couple with a couple of kids and a busy work life, I would take them back to that Pisano and I’d say, “That’s how you guys used to be, just remember how it used to be and look at where you are now, and think about that. Think about that level appreciation.” I would use that picture as a way of provoking those thoughts.

Speaker 1: People’s taste in art is so extremely personal. The painting I love might be something you hate. You might love minimalist architecture. I might get all excited by Byzantine mosaics. Do you think that’s because subconsciously, we’re each actually looking for something that we need?

Speaker 2: Yes, I think that what we love in art tells an awful lot about ourself, but I think particularly it tells us what we’re slightly missing. I think the things that we find most beautiful capture in a kind of concentrated dose, something which we long for inside but don’t have enough of. To just give you a personal example, what I really find beautiful in art and particularly architecture is emptiness. I love peace, harmony, calm. I love this kind of minimalist interiors or I love vistas of the Utah desert. I love the kind of empty canvasses of Agnes Martin. That really gets me going.

Now, what’s going on there? What is it I’m missing? The truth is, that day to day, I’m assaulted by a million e-mails, things to do, panic, worries, et cetera. What I long for and I find so beautiful is something that is the opposite of that. Similarly, I know people … I’ve got good friend of mine who loves Latin American exuberant art. Anything from Brazil gets her going. She wants excitement, et cetera. This fried of mine, she’s Scottish. She came from a very [inaudible 00:08:36] Presbyterian background, very kind of cold family life, et cetera. She’s trying to warm things up. She’s trying to get a sense of drama and collective excitement that she didn’t have enough of.

I think all of us are trying to rebalance ourselves, and that explains taste, and I think that’s why we should go easy on people who don’t share our taste before going, “That’s a bad taste.” Say, “What is it you’re afraid of?” That will tell you an awful lot about why they like that taste.

Speaker 1: That also suggest another very interesting thing to do in a museum or gallery exhibitions, walk around, watch what you love, your reaction to art can be a way to explore and discover things about yourself that you didn’t know.

Speaker 2: Absolutely. It creates ultimately a portrait of who you are. We say in the book that the most important part of the museum visit at the end of the day is the gift shop, when you can pick up a postcard cheaply. Often, one has a relationship with the postcard that you can’t have in a museum with lots of people around the picture. But a postcard, you get it, you put it in your pin board, you look at it in idle moments, you can kind of be yourself around it in a way that often you can’t be with the work actually hanging. All of us or many of us could just assemble our own pictures and make our own little museums that are really going to be our autobiographies. We do this naturally with music. We create playlists. I think it’s just as possible, and just as necessary to create o our playlists of pictures because they are also a guide to what we most need, what we most revere, what most excites us in life.

Speaker 1: This is where we should talk about the other project you did in conjunction with the book. You created an app that’s sort of like a first step toward having a painting playlist you can own.

Speaker 2: I’ve always been thinking about apps and how could we use them in a way that added something to a book rather than just to tract it. We’ve come up with this app which is called artisttherapy.com. You come into it, and there’s a little diagnostic tool which just asks … It gives you various moods. If you click on Work, click on it and it takes you to an image. Let me give you an example of that. I’ve clicked on Anxiety and … Okay, we’re having a bit of fun here because if you click on what would happen next, and we’ve got a work of art courtesy of NASA. NASA’s Hubble Telescope has taken probably some of the greatest works of art. They don’t hang it in museums because of the [snobbery 00:11:05] but they should. It’s a picture of a globular cluster which is part of the galaxy.

The caption that goes with the work basically says, “If you’re a little bit worried about what happens next week, sit with a NASA globular cluster taken by the Hubble Telescope, and it won’t matter so much in a good way.” It’s really about the way the art can give us perspective on things. There’s another picture by … The complaint is, “I find it hard to relax.” I advocate looking at a beautiful picture by Sugimoto, the Japanese photographer of some of North Atlantic on a misty day. It’s just a huge horizon, and feeling small is a wonderful emotion to go for. Feeling small in a vast universe seriously calms down all the complaints of the ego, the anger, the disappointment that comes from not feeling important enough in the world of men and women. Works of art, again has this great ability to take us out of ourselves. It’s very valuable.

Speaker 1: You also created The School of Life in London which among other things offers bibliotherapy, the concept of the novel as a cure. It sounds like in the future, you could imagine seeing a therapist, and the therapist might prescribe you a book to read and a few paintings to go see.

Speaker 2: Absolutely. We’re doing this already. The reason why that sounds strange is that we’re used to thinking that culture, you know, the great works, the great pictures, et cetera; that they don’t have any ability to shed light on the great dilemmas and sufferings, and pains that all of us go through from the moment of birth to death. I passionately disagree, and my whole professional career has been spent arguing against that. A few years ago, I wrote a book called How Proust Can Change Your Life. A lot of Proust scholars came out and said, “How do you mean, Proust can change your life?” The book was utterly serious. It was attempt to say, “Well, of course it can change your life.” If a book matters to us, it’s because it can do something for us, and there’s this word, self-help which is in serious trouble.

When people mention the word self-help, they immediately imagine an idiotic book with a pink cover promising you unrealistic things. It doesn’t have to be that way. Plato’s Symposium is a self-help book. Amazon’s Essays are self-help books. Walden’s Thoreau is a self-help book. We need to rehabilitate that word. We need to become friends again with the idea that the most serious works of culture can alleviate our day-to-day lives and situations. This is not any kind of disparagement or an attempt to attack them. It’s actually a way of doing them proper justice because that’s what their authors and creators would’ve wanted.Speaker 1: Now that you’ve talked about the way you would rearrange a museum, I kind of want to go to that museum. Have any approached you? Are you going to create a museum exhibition?

Speaker 2: Three very, very brave institutions have agreed to go along with this suggestion. The nearest one to you is in Toronto, the AGO in Toronto, a wonderful museum. They’ve gone for this. They’ve said, “Let’s do it,” and they’re allowing me to transform their museum in early May next year into a giant kind of apothecary, a giant kind of dispensing chemist using the art. I would be writing 300 labels for works of art, and rearranging rooms by theme.

Speaker 1: Are you going to rearrange the entire museum?

Speaker 2: I will be rearranging the museum. There will be rooms on love. There will be rooms on death. There will be rooms on all those things. You’ll hear the fireworks from across the Canadian border, but I’m doing the same exercise at the Rijksmuseums in Amsterdam and also a gallery in Australia called The National Gallery of Victoria. It’s an attempt to put this idea into practice and raise some really big questions about how art fits into our lives, and some people wouldn’t agree and that’s fine. I think people worry that I’ll be trying to tell them what to think. It’s not a tool, that it’s an invitation to a more personal relationship with the work of art. That’s the idea.

Speaker 1: More power to you. Thank you so much. That was terrific.

Speaker 2: Thank you. Thanks.

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/apr/25/art-is-therapy-alain-de-botton-rijksmuseum-amsterdam-review

http://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/jan/02/alain-de-botton-guide-art-therapy

https://www.rijksmuseum.nl/en/art-is-therapy

http://www.thefoxisblack.com/2013/10/23/alain-de-bottons-art-as-therapy-will-change-how-you-view-art/

Leave a reply